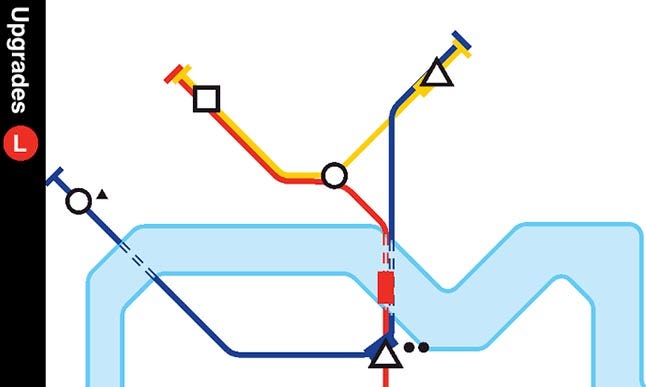

Mini Metro is a game about building subway maps. Stations and passengers appear on a map, and the player builds lines to get people to where they need to be as efficiently as possible.

It has met with commercial success as well as enjoying a run on the festival and awards circuit, culminating in four nominations and one win at the 2016 IGF Awards and one nomination at the BAFTA Games Awards.

Mini Metro was prototyped in a weekend over three years ago. It took ten months to take to Greenlight, another sixteen months to release, and is currently in development for mobile. So postmortem is a bit of a misnomer, as the project is anything but dead!

THINGS THAT WENT WELL

1) Scope

Mini Metro is a game defined by its scope. It’s even in the title! Both of us, Peter and Robert, had worked in the game industry over a decade ago and had since spent a lot of time developing games at home, but had only ever abandoned projects rather than released them.

The original Ludum Dare entry for Mini Metro

The original Ludum Dare entry for Mini Metro

In 2013, when Mini Metro was born, Peter had just started a family with his wife Mary and was a stay-at-home dad. He had a string of half-completed engines and game ideas that were never even started, but wanted to make and actually release a game. For the first time he was aware of how small in scope a game would have to be for him to complete it - he had about an hour and a half during the afternoon when his son had a nanny, and a couple more hours every evening. Robert had a full-time job, and didn't have the capacity to come home from his programming job and write even more code at home.

So we deliberately chose a project that fit within our constraints. We enumerated our many constraints, and drew up a list of the corresponding restrictions we had to put on any game concept.

Strengths:

● Plenty of professional game programming experience.

● Web development experience.

● Good at executing simple, consistent graphic design.

● A long history of playing board games, tabletop wargames, and video games.

● Good at grokking game mechanics.

● A pedantic streak, which helps tremendously when adding the final polish to a title.

Weaknesses:

● Only a handful of hours a day for development.

● Zero skills at producing art assets.

● Zero music and audio skills.

● A pedantic streak, which can mean getting distracted for long periods on trivial tasks.

● No talent at PR and business, and not much drive to get better at it.

We outlined the following hard constraints that any concept would need to fit within:

● No hand-built levels.

● Nothing art-heavy.

● No reliance on audio content.

One thing we immediately found is how ironically liberating it is operating within tight constraints. Not only could we immediately discard 90% of our potential ideas without agonizing for days over the viability of each one, but the constraints themselves inspired ideas. Themes that kept recurring in our concepts were procedural levels and abstract visual styles.

While we discussed a number of ideas that fit within the constraints, we didn’t prototype anything until Ludum Dare 26 in April 2013. Prototyping in a game jam wasn’t something we consciously decided on, but in hindsight it gave us our most important constraint. Any concept we couldn’t have fully prototyped in two days would have been too much for us to fully develop. As it is, Mini Metro has kept us busy for over three years!

2) Giving the game away

We chose to use Unity for our Ludum Dare entry because of the high uptake of the Unity Web Player—like most entrants, we wanted as many people to play our game as possible, and reasoned that a game playable in the browser would get more attention than a downloadable executable.

"It’s impossible to know for sure, but we don’t think Dinosaur Polo Club would be operating now if it wasn’t for that web-playable build."

So almost from the game’s inception it was freely playable online. In the weeks afterwards, when we were discussing how to continue development, we reasoned that keeping it freely playable up to release, and possibly even after release, wouldn’t be such a bad idea. The game we had in the back of our minds was Papers, Please. Lucas Pope had released betas of the game during development; while it’s impossible to know how that impacted the eventual sales, it obviously didn’t preclude commercial success.

The first release of Mini Metro’s playable alpha was in September 2013. We designed the website around the web player. It was front-and-center on the index page, not hidden away behind a button. The game was quick to play, relatively intuitive, and had a virality that the accessibility of the build played into. Hey check out this site, you can make your own subway map! Thanks to that virality the game sailed through Greenlight. It led to a lot of awareness and popularity, much more than we’d ever expected, which contributed to the success of the Steam launch months later.

Again, it’s impossible to know for sure, but we don’t think Dinosaur Polo Club would be operating now if it wasn’t for that web-playable build.

Early Access

Mini Metro is a near-perfect game for the Early Access model. At NZGDC 2015, Peter gave a talk on our experience going through Early Access and outlined the follow attributes that make it suitable:

● Narrow vertical slice.

● Brief play sessions.

● No fixed narrative.

● Procedural levels.

● Segmented content (cities).

In short, we could build it quickly to a saleable state and update it in meaningful ways. It is designed to be played repeatedly, so buying the game in Early Access wouldn’t spoil the experience.

This turned out to be very important for us. Despite the small scope we missed the initial release date of Christmas 2013 by a mile. We ended up taking well over a year to get Mini Metro to its commercial release, and even then it was timed due to “external factors” ... a fancy way of saying we needed some money! Peter started work full-time on Mini Metro around March 2014, soon after it took off on Greenlight, with the anticipation of a full release in late April or May. However game balance turned out to be more complex than anticipated, an interface redesign escalated into a graphical overhaul of the entire game, and we had all sorts of problems scheduling the work on the audio.

A release on Early Access wasn’t something we’d originally considered, but when we realized just how far away a full release was it didn’t take long to decide to go down that route. We released on Early Access in August 2014. It worked out well for the game—Early Access was a natural extension of the open alpha we were already running. The game’s community was already used to regularly-updated builds, giving feedback, and talking with us online. A good chunk of the game’s community made the jump from the free alpha to the paid beta.

Mini Metro earned enough from launch to keep Dinosaur Polo Club running to the end of the year. In the following months it tailed off but was still earning above our expectations. The early release allowed Peter to remain working full-time, and Robert to eventually quit his day job and join full-time as well. Without it we doubt the game would have been finished.

3) Relatable concept

We've spent a lot of time over the past couple of years trying to figure out exactly what it is about Mini Metro that resonates with its players and enabled it to be a success. One thing we come back to is the relatableness of the concept; if someone has had experience with a public transit map, then they'll likely understand what Mini Metro is from a screenshot. The game sells its concept well.

"Inadvertently we made a game that communicates the idea of itself very well. It sells itself not just to the traditional demographics, but because it relates to an everyday concept, 'normal' people get sold on it too. "

We’re not sure if we're over thinking this, but the Dinosaur Polo Club theory holds that for a game to sell itself to a potential player, it needs to quickly communicate exactly what it is. If you're selling to self-identified gamers, it’s easy to communicate a game by relating it to a genre or another game. For example, the vast majority of people on Steam will know what you're talking about if you describe a game as a MOBA, or a first-person shooter, or the love-child of Theme Park, Euro Truck Simulator, and Spelunky (actually, that one might take some explanation). If a game is sufficiently differentiated from other games that it can't be explained quickly and succinctly, it runs the risk of being passed over by people who would have otherwise enjoyed it, if only they had understood the concept. We think Mini Metro managed to do an end-run around this by tying itself to a relatable real-world concept, instead of an abstract game genre.

Inadvertently we made a game that communicates the idea of itself very well. It sells itself not just to the traditional demographics, but because it relates to an everyday concept, “normal” people get sold on it too. People see the marketing for the game—a screenshot, the name, maybe the blurb—and get an accurate idea of what Mini Metro is. This either interests them and they want to know more, or turns them right off and they keep walking.

And we’ve found this is great! Not only does it make our job of communicating what Mini Metro is so much easier, because it communicates so clearly we don’t attract the wrong people and waste their time. At expos the Mini Metro booth mainly attracts people that end up enjoying the game, and likewise the Steam page only seems to pull in people that enjoy it. This has left us with a low return rate, a very high review user rating, and few complaints to answer.

4) The Team

There are two huge skill gaps in Dinosaur Polo Club; audio and art. We never expected to get away without help on Mini Metro’s audio. We didn’t want to phone it in.

No tags.