Excel. That is the most frequently cited writing tool we hear of in the game industry. Excel. For creative writing.

The unfortunate truth is that writing in the game industry is still treated as a minor role, an afterthought. Writers are, by and large, only brought in at the last minute, in order to pen the snappy dialogue that's barked out when enemy soldiers lose sight of the player behind a crate.

But more recently, narrative games have been gaining traction, especially among indie developers. Our industry is telling stories better than ever, whether it's the elegant back-and-forth radio dialogue from Firewatch, the spooky teenage drama from Oxenfree, or the rampant cannibalism in Sunless Sea.

When I founded inkle with serial interactive fiction author and designer Jon Ingold, we knew that writing was going to be at the heart of the company. We never questioned that we would need a specialised writing format to support our projects. Jon was already fluent in Inform 7, the industry standard in parser-based interactive fiction, but we were looking for a format that would support the fluid choice-based system that we were working on. We experimented with a framework called Undum, which had exciting potential, but the authoring system was JavaScript based, and cumbersome to write in.

So, what became ink evolved throughout the first two years and our initial projects. Initially it was very simple - sections and subsections could be linked together with "goto" arrows. Choices were indicated with bullet-like asterisks. Of course, we insisted on having our own weaving-based terminology: we called sections "knots", and sub-sections "stitches".

It worked well enough for our initial projects, including Sorcery!, an adaptation of the gamebook series by Steve Jackson. But, we also evolved the language over time. The biggest change in the early days was the addition of a feature called "weave", allowing the writer to structure intricate branching easily using a hierarchy of indented bullets. It's perfect for writing dialogue, and was pivotal to the writing style in 80 Days.

How ink works

For a full tutorial of ink, see this tutorial. However, if you're just here for a taster, I'll run over a couple of our favourite features.

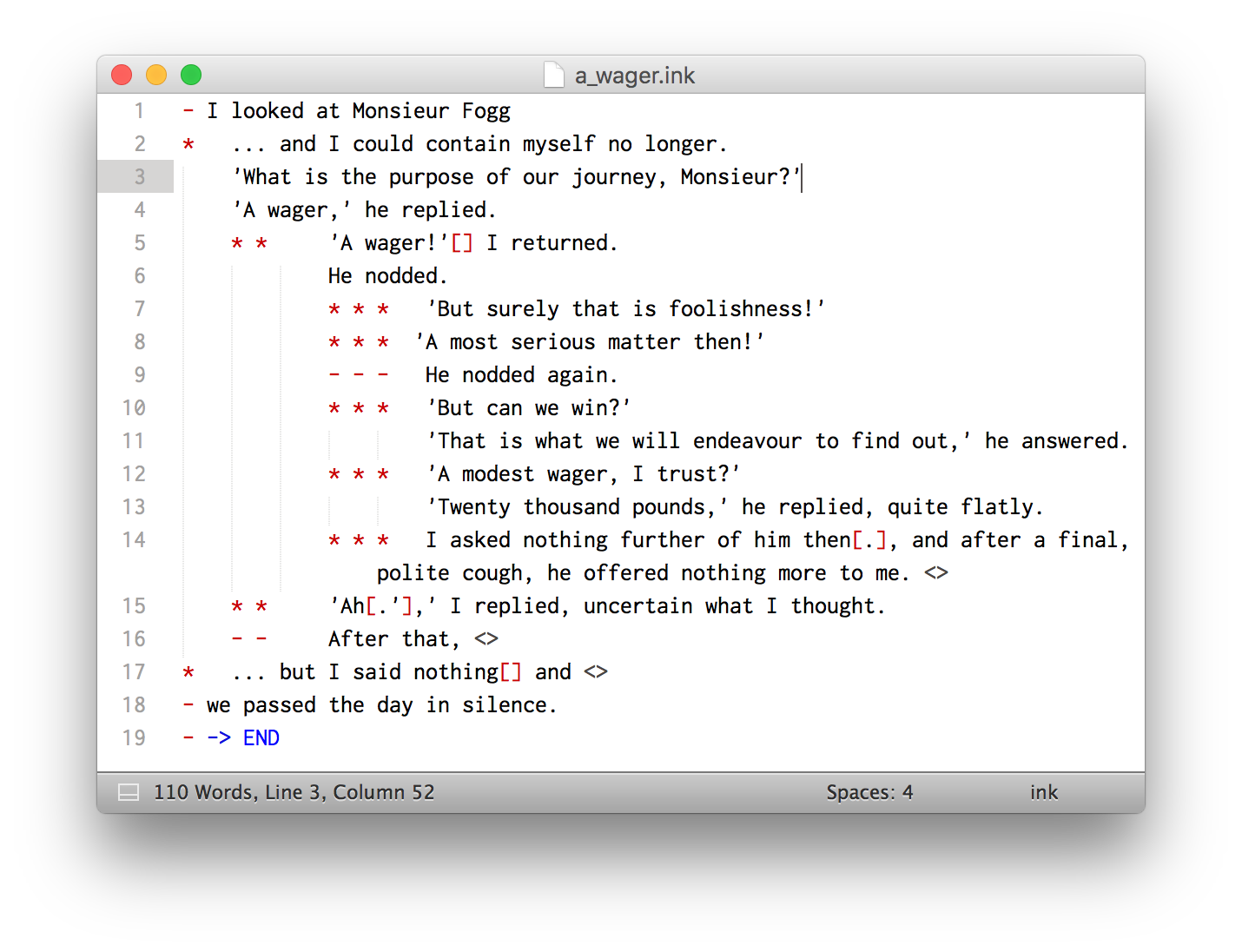

First of all, here's a sample of weave, a feature of ink that's ideally suited to writing natural dialogue, or any content that branches frequently and has forward momentum:

In weave, the flow always moves downwards. It's impossible to have "loose ends", a common issue if you link together your story via the traditional method of "goto" arrows. After an indented section ends, the flow automatically pops out to the next level of indentation.

To see this in action, let's step through the above example.

Broadly, the sub-sections in weave are demarkated by the '-' marks, which we call gathers, since they're also the join points for when the flow runs out. So, we begin with the text "I looked at Monsieur Fogg", and then immediately have two choices, denoted by the single asterisks: "... and I could contain myself no longer.", and "... but I said nothing", which is right down at the bottom.

Let's say the player makes the first choice. Weave automatically steps into the indented section, and produces the text:

'What is the purpose of our journey, Monsieur?'

'A wager,' he replied.

With two new choices:

* * 'A wager!'

* * 'Ah.'

(Don't worry about the square brackets for now, we'll come to those later.)

As you can see, each time we make a choice, we're going deeper into the indentation. By the time we get to the triple-indented choices, we have two more choices, but the flow automatically stops when it sees the triple-indented gather point: the "- - -". After the player makes one of the choices, this is where the flow will continue.

Now, the slightly more tricky part. Let's see what happens when the player picks the choice "'A modest wager, I trust?'", below. After it leads on to the line beginning 'Twenty thousand pounds', we've run out of content at the triple indentation level - all the other content was part of other choices. So, the flow continues to walk down until it finds the next gather point at an outer level of indentation. In this case, the next point it will find is the line: "- - After that,". Again, it runs out of content, so it has to jump outward again, to the final line: "- we passed the day in silence.".

Finally, in case you're wondering what the "<>" does, we call it glue. It automatically makes sure that any content that comes before or after is joined together on the same line, making the final line of content "After that, we passed the day in silence." And that's the end of the section; hopefully you made it out of the weave with your sanity intact!

Yes, it can be a little tricky to get your head around initially, but once you've got it, it's extremely powerful. It's fast, succinct, focussed on the words, and doesn't require the writer to spend a great deal of time working out how to wire everything together.

80 Days' main content was written almost exclusively in weave - Jon had already been moving much of his writing over to the format, and Meg Jayanth loved it. It also perfectly suited a new writing style we were experimenting with. We wanted to evoke the feel of the player writing in a diary, so often we would provide choices that were formed out of partial sentences. Passepartout would start a thought, and the player would finish it, or vice versa.

And that leads me back to the square bracket notation that we skipped over earlier: it's a way of writing choices that began integral to the weave format, and is intended to capture the core similarity between the text of the choice and the text that the game produces as output. For example, in the case of:

'Ah[.'],' I replied ...

The choice text is "'Ah.'", but when chosen, the game displays "'Ah,' I replied". It does this by splitting the text into three parts: the part before the opening bracket, the part within the brackets, and the part that comes afterwards. For the choice itself, it uses the first two, while for the output it uses the first and last.

Again, it's another feature that may hurt your head initially, but also one that is powerful, expressive and terse. Once you're used to it, it's also flexible - you can create choices that aren't echoed to output at all by enclosing all the text within brackets, or the opposite - choices without text in the brackets (there are a couple of those in the sample above.)

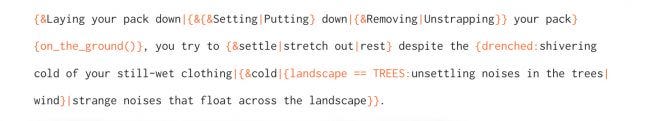

Now, let's take a look at a different sample:

This example is quite different - we're no longer looking at weave, but at a single piece of content (with no choices), that we would argue is approaching procedural narrative.

The extract is from Sorcery! Part 3, in which we have a day-night cycle. The player must choose to sleep if she wishes to regain her stamina each day. Because this is a repetitive action, there's a single piece of content in ink format, but it can come out of the engine in vastly different ways depending on the player's circumstances.

Without explaining every part in detail, what you're looking at is a series of nested pieces of logic: including both cycles and conditionals. Each of those logical pieces is rather simple on its own. Each time the player reads the content, she'll get different text from a cycle block, to vary it and keep it interesting. Meanwhile, the conditionals allow us to present different variations depending on, for example, whether the player is in a forest, or whether they happened to get very wet somehow earlier that day.

The overall result when piecing these bits of g