For all volumes of my book series, The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, I asked interviewees to sketch the layouts of their offices from that time. A surprisingly high number of readers don't get why I did this. In fact, from what I can tell, most readers seem to regard the energy of acquiring the maps as somehow wasted. To paraphrase and amalgamate comments from a bunch of reviews: "What is up with the author's strange obsession with office layouts?"

Anyone who needs to ask why has obviously never read Philip K. Dick's The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch. The purpose of the layouts is to induce a hypnotic trance-like state and project oneself, astrally, through the barriers of space and time, so as to experience vicariously the history of game development within a mutually consensual hallucination.

As I state on page 273 of Volume 2:

"I want every reader, when absorbing these interviews, to really be there. Can you do that for me? As you read the words which describe these places, take a moment and close your eyes: notice the desks and windows, imagine them around you as you hold this book. You're not sitting in your home or on transportation, you are in that game developer's office, the papers around you contain concept art, the air is rich with instant-ramen vapour and nicotine - YOU ARE IN JAPAN RIGHT NOW."

Failing that, the layouts also reveal a lot about a company's workings, how it functioned, how it structured its workflows, how it regarded certain employee positions... Some make no sense whatsoever, and are reflections of archaic computer technology. Hard drives needing a "clean room" for example, forcing programmers to walk a flight of stairs between their desks and workstations.

Get 50 people to draw 50 maps and you'll likely find 50 different ways to run a company.

I am giving permission for these maps to be reproduced elsewhere, on websites like MobyGames or Wikipedia, or in print media, on the following conditions: the original map artist is credited, and an Amazon link to Volume 2 of my books is provided with cover image, explaining this is the source of several maps.

The following maps are presented in a semi-random order, and are sourced from Volumes 1 and 2, and the as yet unpublished Volume 3.

MAPS TO THE STARS

Capcom by Kouichi Yostsui (creator of Strider)

Drawn by a pixel artist this map itself is quite beautiful, and shows how much emphasis Capcom placed on creating graphics. Ten desks in a dedicated room, taking up at least 1/3 of the entire floor, with a comparatively smaller planning room adjacent. There's also the typical WC and "crash room" for tired staff to sleep in. Top of the map is Tokuro Fujiwara, creator of Ghosts 'n Goblins, in his own office.

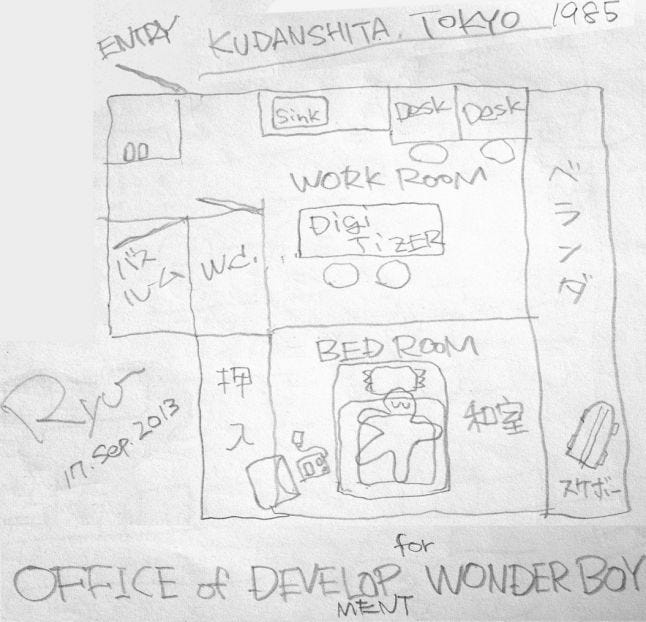

Westone by Ryuichi Nishizawa

This is where the original Wonder Boy was developed, later remade by Hudson as Adventure Island. It was a rented apartment, and the abandoned skateboard on the veranda directly led to the skateboard mechanics in-game. In the centre is the Digitizer graphics utility loaned by Sega. This map shows that even humble surroundings can lead to timeless classics.

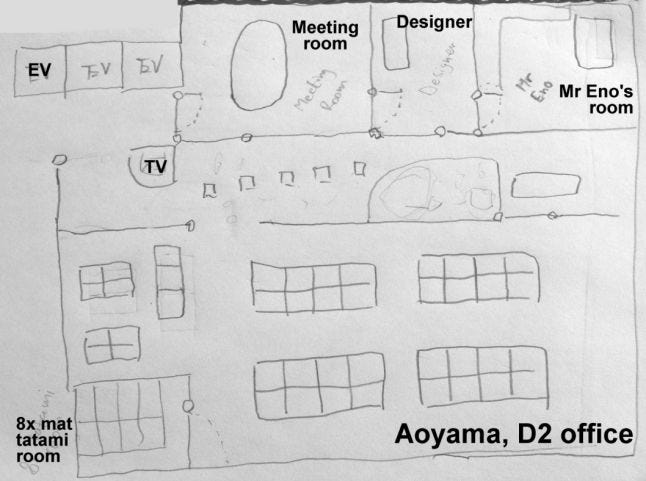

Kenji Eno's WARP offices by Katsutoshi Eguchi

KE: "This was in Aoyama, on the 4th floor. There's three elevators in the entrance. There was a receptionist, and there was a TV. The WARP logo would loop on that. In this next area there were five raised platforms made of silver, like large stepping stones, surrounded by gravel or pebbles. It resembled a zen temple. This is a lake, or like a pond, and this area had a shrine or garden-like design. They had one of those wooden temple ornaments. They're made of bamboo and slowly fill with water, and then go *clonk* when full. You would walk along these stepping stones, and it was like Enemy Zero, in that your steps would make a sound, like *kon-kon-kon*. While the water would make a sound like *chara-chara-chara*.

"Adjacent this area were three rooms. This was the entrance to the meeting room. Here was where the designers were, and this was Eno-san's office. To get to Eno-san's office you would go down all the stepping stones and then past the Japanese garden display, and that's how you pass through the office. He could hear the *kon-kon-kon* sound as you approached. It had a very Kyoto-style, zen garden feel to it. It cost twenty million yen. Photographs of this office were shown in business magazines in America, as examples of office design. Works of design art.

"Here in the corner they had a tatami mat room, about 8 tatami in size, that was designed so people could have a sleep. Because the programmers were working very late. But everybody would just sleep at their desks, put a jacket over their heads and just crash out. There was always someone working at these desks, 24 hours a day. Essentially the people lived in the office. Eno-san would basically live in the office. They were not made to stay in the office, and I don't think the hours they had to work were that long, but because it was rendering video - especially back then it could take 20 plus hours - what you would do is, you would hit 'render' for the bit you were working on and then just go to sleep. Then four hours later you'd wake up, go to the next one, hit render, and that's what a lot of people did."

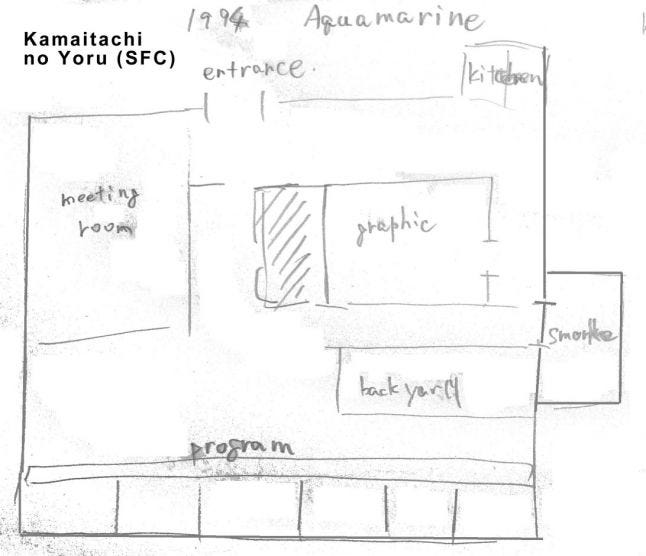

Aquamarine (Kamaitachi no Yoru) office by Yasuo Nakajima

Kamaitachi no Yoru was a landmark release for Japanese visual novels, so it's sad to consider the company folded, despite the game itself seeing multiple re-releases right up to the present. Note the smoking room, which is common for a lot of Japanese developers, even today (NudeMaker has one!). YN: "Although I was doing work for Chunsoft, I was working at a different company office. <sketches> It was like this. We had this separate room for taking a smoke break. <laughs> And there was a partition here... This was the meeting room, this was the graphic section I think. The programming team was here. And there was a storage area here. And there was a kitchenette for making tea and coffee. I was there until around 1998."

Athena office by Aziz Hinoshita (company responsible for Dezaemon series)

The entire company existed on a single floor and at first seems quite organised, until you notice the large sections marked "junk" on the left and bottom sides. Apparently old computer equipment was just haphazardly piled up, slowly turning yellow from cigarette smoke. Employees were allowed to smoke at their desks, and the bottom of the map has a sketch complete with ashtray. As expected there are bathrooms, a kitchen, and sleeping area, for staff who basically lived in the office. Imagine living out the early 1990s entirely from this little bubble.

Chunsoft (Dragon Quest III) office by Manabu Yamana

Another landmark series in Japan, Dragon Quest is phenomenally important. Two things stand out from this sketch: the meeting room is huge, likely to accommodate the many members of Chunsoft, (developer), Enix (publisher), and Nintendo (platform holder) who would all meet to discuss the next instalment. Secondly, the development area is very professionally laid-out and expensive, featuring specially provided HP 64000 workstations with In-Circuit Emulators for interfacing with Famicom hardware. A lonely PC-98 sits in the corner.

Compile office by Yuichi Toyama

Planning, graphics design, and sound all get their own separate enclosures at Compile and, assuming this is reasonably to scale, they had quite a large air-conditioning set-up. Furthermore, individuals such as Yuichi Toyama appear to have their own separate work areas.

TechnoSoft by Mitsuakira Tatsuta

Not much is given away here other than the fact TecnoSoft had a mysterious "secret room", and the fact its sound department occupied a (quite literally) central role. However, compare this hand-drawn sketch with the following map of the same office...

TecnoSoft by Naosuke Arai

It's flipped round 90 degrees counter-clockwise, but it's the same area. It also highlights the fact that memories sometimes fade - the WC is in a slightly different position now. We also see that Thunder Force had its own section.

dB-Soft by Yasuhito Saito

This is the company that made Leila on Famicom; best known in Japan for its computer releases, nothing dB-Soft ever made came to the West. Like a lot of computer game developers it started off as a PC shop, incorporating this into its daily running. The bottom area is where development took place, on a bank of extremely expensive HP 64000 computers, much like Chunsoft. The little sign by the door shows you must remove your shoes. No smoking was allowed in this area, because the computers were too expensive to risk damaging!

Data West by Yasuhito Saito

A simple but effective layout, with programmers on the one side, graphics in the middle, and Saito creating the music on the opposite end. The company mainly created adventure games and 2D shmups for computers.

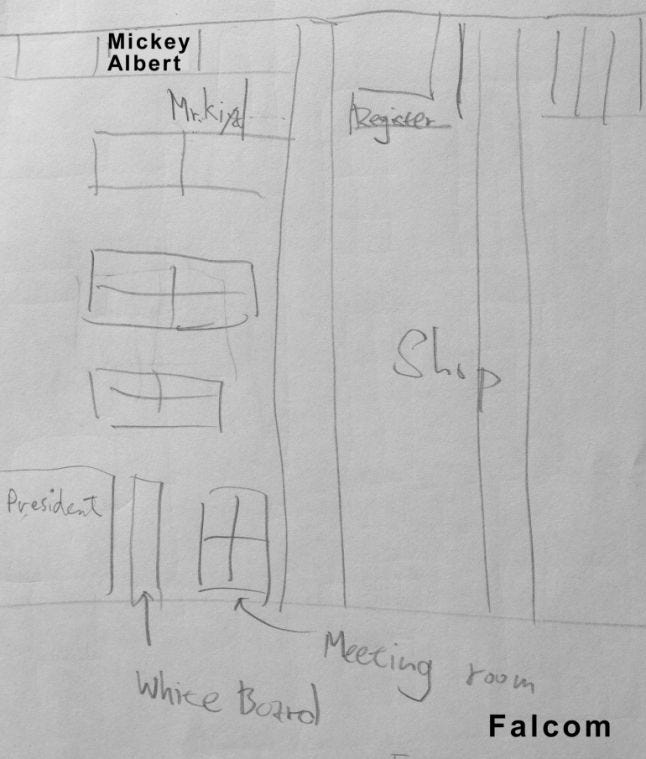

Early Falcom by Mikito Ichikawa (aka: Mickey Albert)

A sketch showing early Falcom by Ichikawa, who worked part-time when he was only 14! This would be around the mid-1980s. Notice how large the shop area is, effectively taking up 50% of the floorspace.

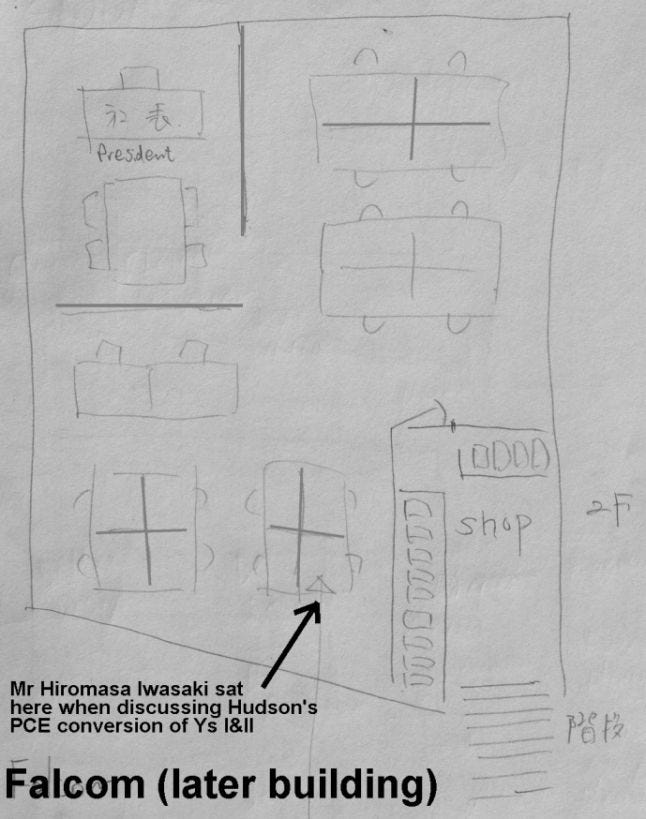

Later Falcom by Jun Nagashima

We're entering the 1990s and a new office for Falcom, and notice how drastically the shop has been downsized, with most of the focus on new game development. On the lower side we can see the area where negotiations for Ys I&II on the TurboGrafx CD-ROM were done by Hiromasa Iwasaki.

Game Arts 1 by Kohei Ikeda

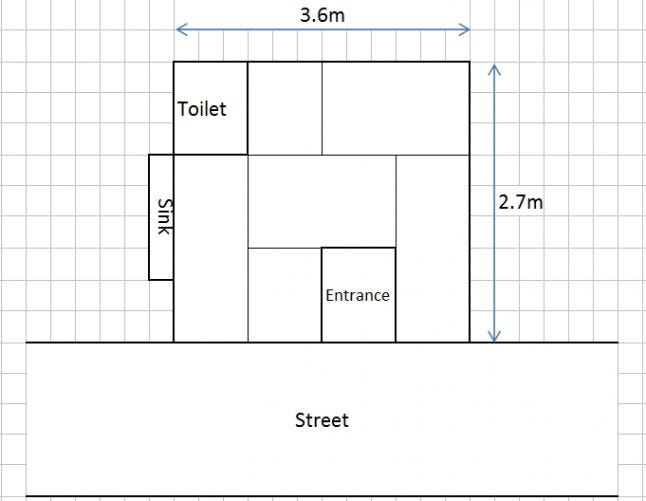

The first Game Arts office (9.72sqm), from Dec 1984 to Feb 1985. The founding members were Misters Matsuda, Y-Miyaji, Ikeda, Uchida, T-Miyaji, Uesaka, Shimada, Okabe, and Koyama. A