[The GameDiscoverCo game discovery newsletter is written by ‘how people find your game’ expert & GameDiscoverCo founder Simon Carless, and is a regular look at how people discover and buy video games in the 2020s.]

Welcome to a special edition of the GameDiscoverCo newsletter, folks. This one started with the concept that procedural/roguelite games continue to shine super-bright in terms of game discovery. (Streamers love them!)

And we’re a big fan of the Spelunky series - the inventively brutal 2D platformer which was a modern pioneer of the ‘different behaviors every time for more replayability and fun’ genre. (Also, Spelunky was the first procedural game to play with the ‘Daily Run’ concept, where everyone gets the same seed to compete against each other.)

Do you know where we can learn more about the franchise? Via creator Derek Yu’s excellent Boss Fight Books tome documenting his creation of the Xbox Live Arcade ‘HD’ version of Spelunky. (The game has spawned a well-received sequel, of course, but the original has been converted to a host of other platforms - including Nintendo Switch just in the last few weeks.)

For anyone who didn’t know this book existed, it’s described like this on Boss Fight Books’ product page: “Spelunky is Boss Fight's first autobiographical book: the story of a game's creation as told by its creator. Using his own game as a vehicle, Derek Yu discusses such wide-ranging topics as randomization, challenge, indifferent game worlds, player feedback, development team dynamics, and what's required to actually finish a game.”

It’s one of my favorites from the entire Boss Fight Books series on classic games. I’ve known Derek all the way back into the TIGSource days, and find his design-centric writing about Spelunky - originally released in 2016 - to be wonderfully educational and precise. So I asked Boss Fight’s boss (!) Gabe Durham and Derek if we could do two things:

Print some extracts from the book - for all my GameDiscoverCo free newsletter subscribers: they’re on designing Spelunky’s monsters for epic procedural moments, and on finishing your game (a vital thing!)

Make the full ‘making of Spelunky’ eBook available to GameDiscoverCo Plus paid subscribers - where it joins the ‘Complete Game Discovery Toolkit’ eBook written by me, as well as a host of other perks.

And they kindly agreed to both! So if you’re a Plus member, the entire Boss Fight Books ‘Spelunky’ eBook is now available to download (PDF, MOBI and EPUB) in the Plus data & eBooks back-end. And… for everyone, here’s two key passages from Derek’s book:

Designing Spelunky’s monsters for ‘complex moments’

In designing new monsters [in Spelunky HD], I not only wanted to add more complex interactions and challenges, but I also wanted to make the world feel more alive. The human mind excels at finding patterns and making connections, so just adding a few variations on existing monsters gives the impression that they have families.

When you see that a tiki man is really a caveman with a mask and a boomerang, you start to wonder if they belong to a tribe where the tiki men are high-ranking members. Other patterns quickly play into that notion, like the fact that tiki men are rarer and only appear in the Jungle, whereas cavemen roam around in other areas, too. Tiki men are already more difficult monsters than cavemen, but these little details cement their elite status and therefore their place in Spelunky’s world.

This “alive” quality doesn’t depend so much on the complexity of each monster’s artificial intelligence. Take, for example, the way players associate the four ghosts in Pac-Man with aggression, ambush, capriciousness, and stupidity.

In reality, the behavior of the ghosts is determined by simple algorithms that target different tiles to move to based on each character’s position. When these behaviors play out together on the same map, however, it seems as though the ghosts are working together, with Blinky chasing Pac-Man into the ambush of Pinky and so on.

I applied a similar principle to Spelunky: Combine simple behaviors to give the impression that the monsters are working together. This not only creates challenging situations, but it also makes the world feel more like a living, breathing ecosystem.

Wherever possible, I tried to add monsters that attack you from new directions, so that when they were paired with existing monsters the attacks would feel coordinated. In the Jungle, for example, the snail blows acid bubbles that float upward - you can often see these floating up from gaps in the floor, making gaps more dangerous to jump over or into.

And in the Ice Caves, the woolly mammoth spits a horizontally-moving freeze shot that creates a cross fire with the UFO’s downward-moving projectile. Both the snail’s bubble and mammoth’s blast are also used elsewhere in the game.

The bubble floats up from acid pools in the hidden Worm level and the freeze shot can be fired from a freeze ray the player can acquire from a shop. Giving its inhabitants a shared language is not just a time-saving measure, but another way to make the world feel cohesive.

One of my favorite Spelunky stories is a great showcase of how simple behaviors can lead to complex moments. It comes from Tom Francis, a former editor of PC Gamer and now a fellow game developer, about the time Tom was in the Black Market and watched a tiki man wander empty-handed into one of the shops.

Tom sees the tiki man pick up a boomerang that’s for sale in the shop. “For a split second, I am amused,” he writes. “He’s going to buy a new boomerang! Silly tribesman, you don’t own material wealth!” But then it dawns on him that something terrible is about to happen, and he scrambles away to a safe corner to avoid what he calls the “shopstorm”:

“All nine shopkeepers hurl themselves into the air and start firing their shotguns in random directions. They kill the tribesman. They kill two other tribesmen. They kill frogs, pitchers, snails. One kills the slave he was selling, another kills his own dog. Two of them throw themselves to their deaths in the excitement. Four of them throw themselves into a pit, where their bursts of buckshot cut each other to ribbons.

When the blasts quiet down, I crawl slowly out of my hiding place and walk carefully through the empty shops, collecting everything for free.

What happened here was: the tribesman walked out of the shop. He walked out of the shop with the shopkeeper’s boomerang in his hand, and he walked out of the shop without paying for it.”

What makes Tom’s story so cool is that a number of disparate systems came together in just the right way to write its plot. First, a tiki man had to lose his boomerang, either by getting hit by something (like a tiki trap) or by throwing it at Tom. Then the tiki man had to walk into one of the Black Market’s shops. Finally, the shop had to be selling a boomerang.

What happened next was the tiki man’s “pick up a boomerang and walk away with it” system met with the shopkeeper’s “get incredibly angry if an unpaid item leaves the shop” system and all hell broke loose. Tom’s thorough understanding of these systems takes nothing away from his fascination with it. Actually, the opposite is true—his understanding only deepens his enjoyment.

Traditional, linear, static narratives will always be important in video games, but these personal tales are the ones that, to me, separate the gaming experience from other art forms. Unlike fan fiction, where the audience is creating stories based on their favorite worlds, game players are living them.

And in the context of these stories, the random number generator is akin to Fate, setting up scenarios that at times seem too incredible to be anything but scripted. No wonder game players are known to send prayers and curses to the “Random Number God” or “RNGesus.”

It’s easy to add more and more things to a randomized game and rely on what I think of as the “free value” that randomization offers. In a game with randomized levels, people will keep playing just to see what comes up.

But to make it more than a glorified slot machine requires putting together a collection of systems and rules that is worth understanding, behind a world that feels interconnected.

If you can manage that, a simple story of rescuing a troll from a pit and making it your friend, an “EPIC MOMENT” when a spider was killed by an arrow trap, or a deadly shopstorm becomes something as meaningful and memorable as hours of dialogue and scripted cutscenes. Sometimes more so.

On the art of finishing a game

In September 2010, I wrote an article for my game-making blog called “Finishing a Game.” It’s a strategy guide of sorts for making a video game, although it could probably be applied to any creative endeavor. The thesis of the article is that finishing is a skill as much as being able to design, draw, program, or make music, and that finished projects are more valuable than unfinished projects.

Most creative people are familiar with the first part of making something, and it’s easy to mistakenly assume that the rest is just more of the same. It’s akin to repeatedly climbing the first quarter of a mountain and thinking that you’re getting the experience you need to summit. Or running a few miles and thinking that you can run a marathon.

In truth, the only way to learn how to summit mountains, run marathons, and finish making games is to actually do those things.

The article consisted of fifteen tips on how to finish a game:

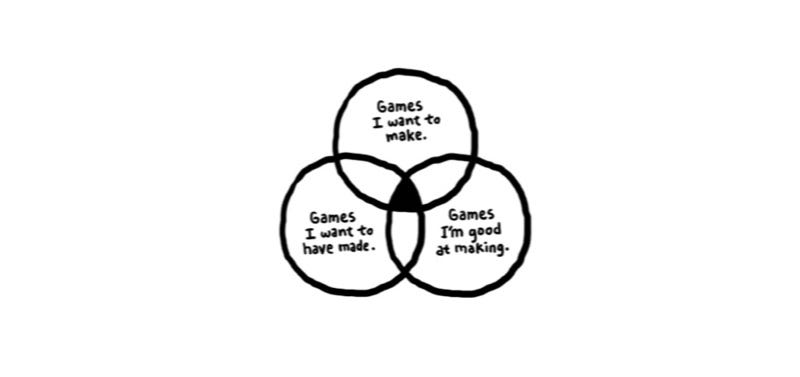

Choose an idea for a game that satisfies three requirements: it’s a game that you want to make, a game that you are good at making, and a game you will wish you had made.

Actually start the damn game. Writing design documents and planning doesn’t count.

Don’t roll your own tech if you don’t have to.

Prototype.