What if I told you there was a model that could potentially fund games -- both initial funding, and their continued development? I'm here to share an exciting new challenge for game developers: building play-to-earn / play-and-earn games.

Axie Infinity has been making headlines in the news cycle for a variety of reasons: its token’s price action, how it 'creates work' for people globally and its incredible profit surge, surpassing revenue from both Ethereum and Bitcoin combined. (84.9 million USD in funds for its treasury!)

I’d like to zoom out from the news cycle and write something a little more lasting: a survey of how games have monetized hitherto, how play to earn acts as a new model for monetization, and how this form of monetization can change the relationship between devs and players.

I’ll bring in examples from various video game economies along the way.

First, let's establish a framework for understanding video-game monetization, discussing free-to-play, premium games, in-app purchases, DLCs, and play-to-earn.

Towards the end, I’ll write about how play and earn can lead to incentive alignment between developer and player.

Games as Products

Games are products that require money to keep them going — server costs, the cost of hiring engineers and developers to build them, etc. To support a game (particularly an online one) into perpetuity is expensive, even (and especially!) ones with 200 million user accounts at their peak. (See Club Penguin.)

Fig 1: Club Penguin, an MMO that monetized using paid memberships. It was acquired for 350 million USD++ by Disney and yet shut down in 2017.

Keeping a (Game’s) Engine Running

Game developers have a choice of how to monetize and fund their games. They must find ways to (1) fund initial development, (2) make revenue from the game that outstrips expenses.

So they monetize.

My claim is that the mode of monetization in video games can drastically affect the end-user experience of the video game, and I’ll break down the different incentives that developers will encounter based on the choices they make re: monetization.

There are free-to-play games (F2P), and there are premium (P2P, or pay-to-play) games. We define free-to-play as ‘free-to-start’, providing some level of gameplay without requiring any cash investment from the player. In contrast, a P2P game requires you to invest up-front in order to meaningfully engage in the game. The line between F2P and P2P has blurred in recent years, but this distinction is clear enough for our purposes.

Free to Play

Free-to-play means: no up-front cash investment is required for you to begin playing the game.

Onboarding might involve registration of an account, downloading an app onto your phone, or even simply visiting a website with a catalog of games (itch.io, for example).

Free-to-Play games monetize in a variety of ways — sponsorships, advertisements, and most notoriously, in-app purchases which can be either cosmetic or have an effect on gameplay.

Fig 2: It’s raining! Now you can view an advertisement to extend your boost.

Challenges: advertisements can break the flow and frustrate users. Rewarded ads do a better at resolving this dissonance, but still take away from play-time. Cosmetic items don’t sell nearly enough in most games to fund the development of the game, and every gamer is familiar with this phrase: pay-to-win.

Premium Games

Premium games are games that you pay upfront for.

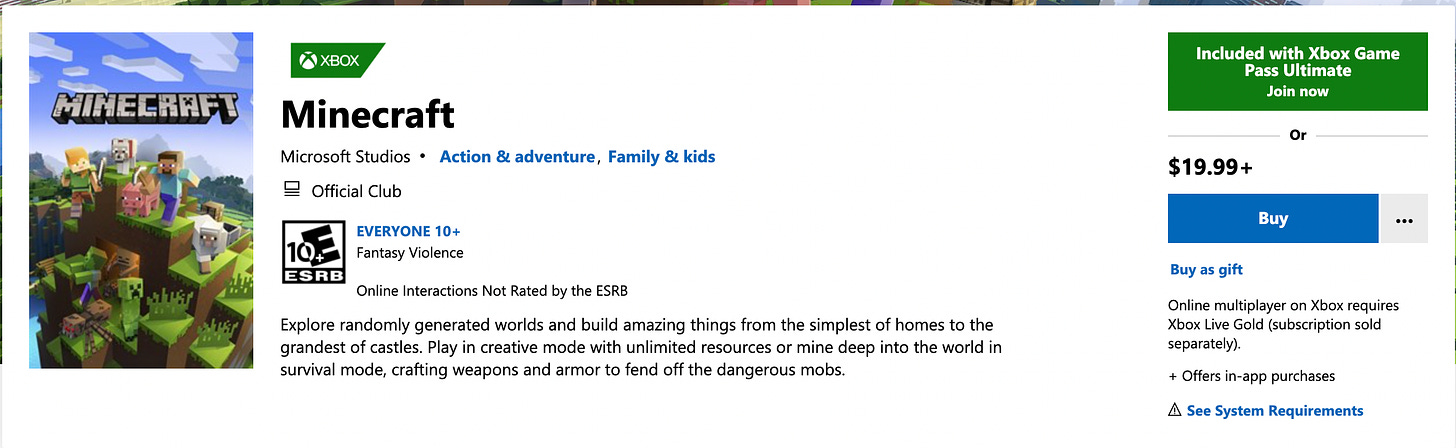

When you want to play these games, you might go to GameStop to buy The Witcher 3 for 18.99, or you might buy Minecraft from the Microsoft store for 19.99, or download Stardew Valley on your iPhone for 7.99 USD.

Fig 2: Familiar with this screen?

You could also buy, and then pay a subscription to continue playing in the game, like World of Warcraft. Yes, the game that has had more than 9 billion USD of revenue as of 2017. You’ll see more WoW in other articles, too!

Fig 3: Your subscription has expired. Renew?

The Challenge of Monetization

Both F2P and Premium games can have multiple monetization features: a free-to-play game can be free-to-start while allowing membership subscription (Runescape) or be free-to-play while allowing a one-time membership purchase for more content (BattleOn). A F2P game can show you advertisements (any hypercasual game on your phone) and allow you to buy cosmetics (DotA 2, League of Legends).

In-App Purchases

Microtransactions. So many forms.

Denial of access to game - You’ll be in the game, and you receive a popup saying ‘oh, too bad you ran out of energy. Want to give us $1.99 to keep playing?’

Cosmetic - Here’s some items that make you look cooler than other people. And you basically have to pay to get them.

Powerups - Here’s some items that make you stronger than other people, faster.

It goes on, and on.

I do believe if we zoom out from this frame of “how can we make the most money from the player”, we’ll be able to discover new modes of monetization that (1) grow game communities and (2) derisk the game development process. I believe relying solely on monetization via IAP / microtransactions is a local maxima which erodes trust of players over time.

Even cosmetics aren’t immune from the animosity towards microtransactions. NPR wrote this piece back in March, with a great insight:

Microtransactions aren't just about the cosmetic upgrades; often, they're important to the actual gameplay. Dr. Ellen Evers, a marketing professor at the University of California, Berkeley who researches microtransactions, says that can take away a video game's magic.

…

“The implicit assumption is that by playing the game and building up your character, you're supposed to get better," says Evers. "Microtransactions basically make the game easier. They violate those rules and norms that are part of the game."

The magic circle of the game is violated when you press too heavily upon that assumption, which can disengage players. Microtransactions aren’t terrible, but game developers have to be very careful about using them.

Combating Dissonance

With these existing models, developers have to walk a tenuous line. Why?

As they develop the game, any feature has to serve bottom-line revenue somehow. That’s just how the economics of game development work right now. Let’s raise LTV, reduce CAC. Find ways to cash in on our time, and resources spent developing the game. It can seem like fun and sustainability move in two opposing directions.

Monetization often becomes something that a player dreads (advertisements), or merely tolerates (ok, I can play Clash Royale, and come up against difficult enemies once in a while. But as long as I get to play).

In the same way, when players play the game, they can feel like it draws away from their financial goals. (The closest we can get to integration and alignment is: “I play to destress from my job and work.”)

But moving past that is going to allow for a re-valuation of values: it is an opportunity for designers to pave the way for game economies that allow skilled users to engage in high leverage work, and regular users to enjoy the game, with the accrual of value as a by-product. Work that can fund “nappies and milk for their babies, to shoes and shirts to wear to job interviews.”

Play to Earn / Play and Earn games can help resolve that dissonance and tension. Building Play to Earn experiences means giving people 'work in the metaverse', and so playing can become more of an investment and less of an expense. Cool, huh?

On Gold Making, and Leveraged Work

In World of Warcraft, there are many ways a player can make gold. In fact, there are entire websites dedicated to how you can make more gold! Killing monsters one by one is one of the slowest ways to do it.

Let’s talk about some ways people make gold in World of Warcraft.