Game Design Deep Dive is an ongoing Gamasutra series with the goal of shedding light on specific design features or mechanics within a video game, in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Check out earlier installments on the the action-based RPG battles in Undertale situational awareness and player frustration in GRIP, and building cooperative play in Overcooked.

Also, dig into our ever-growing Deep Dive archive for developer-minded features on everything from rocket jumping in Rocket League to Dying Light's Natural Movement System.

Who: Adam Hines, co-founder of Night School Studio and game director, and Kevin Riach, game designer and producer of Mr. Robot Ep1.51exfiltrati0n released on August 17th

KEVIN RIACH: While Night School Studio was founded back in 2014, Adam and I only started working together in July of 2015 on the studio’s debut title, Oxenfree.

Adam acted as the sole writer and game director on the project, while I came on late in development as a contract designer to help complete the game on time. The choice-based adventure game released this past January and it’s available on your PlayStations, your XBoxes, your Steamses, GOG’s and any other website place that dabbles in video game wares.

Adam acted as the sole writer and game director on the project, while I came on late in development as a contract designer to help complete the game on time. The choice-based adventure game released this past January and it’s available on your PlayStations, your XBoxes, your Steamses, GOG’s and any other website place that dabbles in video game wares.

After Oxenfree’s release, we began brainstorming various concepts for what we should tackle as our next project. The studio was initially founded as a small team that could focus on the intersection of story and interactivity.

We knew we wanted to take a more unconventional approach to telling an interactive story, and were playing with the idea of an entire story told through text messages.

Soon after, we were approached by Universal about making a game set in the Mr. Robot universe, and the two ideas just seemed like a natural fit for each other.

The team, 6 full-time people and 2 contractors, built the game over a 6-month development cycle. Not long after development began, Adam’s old colleagues at Telltale Games (where he helped write The Wolf Among Us) were brought into the fold, and Mr. Robot Ep1.51exfiltrati0n (hereafter referred to as Exfiltrati0n for everyone’s sanity) was born.

What: Modify Oxenfree’s free flowing conversation system to simulate real time text conversations

.jpeg?width=250&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) KEVIN RIACH: When compared to similar choice-based games, the first thing that stands out to many about Oxenfree is the natural way in which conversations flowed together.

KEVIN RIACH: When compared to similar choice-based games, the first thing that stands out to many about Oxenfree is the natural way in which conversations flowed together.

After all, it was the game’s core design objective and we worked tirelessly to get it to accurately simulate the speech patterns of real world conversations. So when making Exfiltrati0n, we knew it would be crucial to nail the very specific rhythm and cadences of real life texting in order for players to fully invest in the story.

ADAM HINES: At first it seemed fairly easy to pull off, but, as it turns out, we are quite stupid. For one thing, every living creature that would be at all interested in playing this thing knows what texting is, and experiences the act of texting to such a pervasive (perversive?) degree that if even one detail is slightly off, the entire charade collapses like so many ill-advised “fake” bits of technology we’ve all seen in other tone-deaf media.

I’m sure you can recall some episode from one of the seemingly endless statecraft procedurals that cheerfully featured some “internet site” called YourSpace, a garish slide-show crafted ostensibly by a dog after watching humans use computers for a week.

On the other side of the spectrum, take the 1996 horror movie classic, Scream. The “Ghostface” mask they used in the movie wasn’t legally cleared until days into production because the 95% accurate copies they’d made weren’t EXACTLY to the director’s liking. So they shot the mask they had, praying they’d be able to track down its copyright owners to clear it in time. It was worth the risk.

The point is, it’s a fine line between authenticity and embarrassment, and it’s the details that push that from one to the other, and if you don’t have the time to get those details right, you’re better off doing something useful with your life like pave roads. I know I’ve considered it.

Why?

.jpeg?width=275&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) ADAM HINES: The show Mr. Robot is about a couple of things, but one consistent bit of thematic stuffing is how technology and people intersect in often basic, sometimes beautiful and more than occasionally damaging ways.

ADAM HINES: The show Mr. Robot is about a couple of things, but one consistent bit of thematic stuffing is how technology and people intersect in often basic, sometimes beautiful and more than occasionally damaging ways.

We pitched to Sam Esmail (the show’s creator and overlord, responsible for writing most episodes and directing the entirety of Season 2) and the folks at USA a few ideas around this concept, and eventually landed on a mobile game that takes place entirely within the structure of a texting app.

You’d interact with the show’s characters during a whirlwind week of social engineering and dubious morality, coming out the other side a little more alert to the unseen efforts of the hacker collective known as fsociety and their attempts to destroy E-Corp, an evil tech conglomerate and one of the largest companies in the world.

To accomplish this, the app would effectively be a skin of sorts for an interactive script; the player would get a text, and from two or three pre-written choices steer the conversation in whatever way they saw fit.

So, our goal, all said, was pretty straightforward: this game should feel like a real app - something genuine human beings that breathe air and drink water and all of that mammal stuff would actually use - and the act of sending and receiving texts should be fun! The first issue - feeling real - meant from a writing perspective a few things that might seem counter to a good gameplay experience.

Texts shouldn’t come through like a smoothly flowing, predictable stream, oh no! Texting another person should be jumpy, awkward… people should disappear for minutes at a time and rattle off different topics herky-jerkily. You shouldn’t know their name until you learn who it is. They should make spelling mistakes and be hard to understand sometimes. And you should be able to carry on multiple conversations, learning information in one thread and using it in another.

Idles and Waits

ADAM HINES: To write all of this nonsense meant keeping track of what the player knew, when they knew it, when they could talk about it, and controlling the gaps of time between texts to create a believably real series of incidences. One trick to making conversations in video games feel natural is to have the person(s) you’re talking to not shut up, even when you’re deciding what to say. We call these idles.

In simulations of real life, in-your-face speaking (in-your-face not like snowboarding down a mountain holding a Mountain Dew sort of way, but in-your-face meaning literally in-person), these work beautifully, filling the time when you’re making a decision with life-like chatter.

In texting, it’s not so simple; they should text you while you’re texting back, certainly, but it’s not uncommon in this fast paced, jet setting world we all live in to respond to texts hours, sometimes days after getting one. And if the player is that lazy, the game’s characters - who, remember, are all desperately needing things NOW, not later - should call them out on it, and through increasingly frantic means. So we added another “tier” of idles called waits. These will trigger when you just sit on your phone and don’t respond for a while.

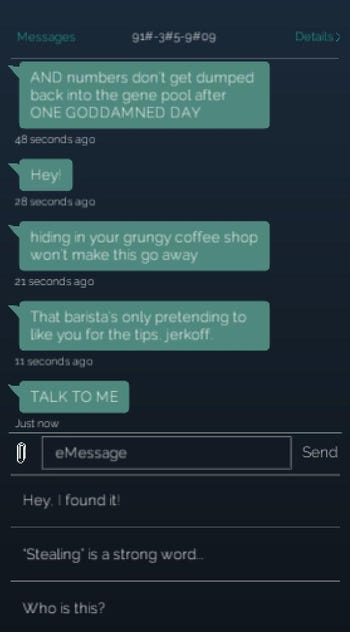

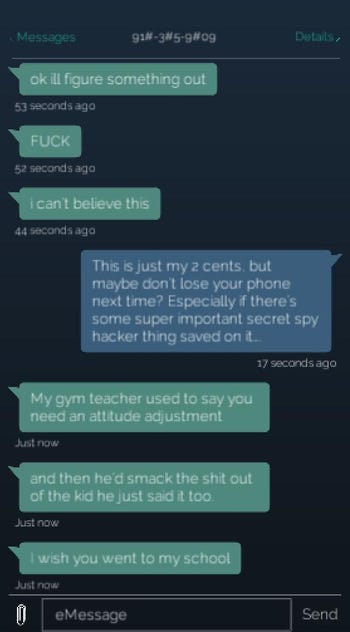

Here’s an example from early in the game. Darlene first texts you, saying that she knows you stole her phone.

At this point, you can respond, and while your choices of what to say come up, she’ll continue berating you.

She’ll now politely wait for your reply, and stop texting you for several minutes. If you haven’t responded by the end of that time, she’ll pipe up again.

KEVIN RIACH: The system itself is deceptively simple. Our scripting system allows for multiple threads of dialog to run parallel with each other. Choices are stored separately from the characters dialog, and when a choice is made, it simply overrides any stored dialog. Hopefully this ebb and flow makes the whole thing feel like a real person, and not a system eliciting an echo.

Callbacks

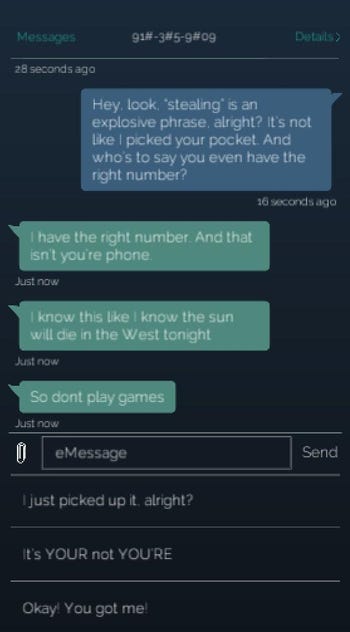

ADAM HINES: Another way we try and trick your brain into thinking these 1’s and 0’s are things that actually care about you is -- whenever possible and appropriate -- we remind the player of a previous choice they’ve already made. So, as an example from the same conversation with Darlene:

If you say, “It’s YOUR, not YOU’RE” to Darlene, the game will set a flag to remember that. But that’s not the important part; the important part is when that information is recalled. Like, for instance, later in the conversation, you can say:

3) Don’t lose your phone next time…

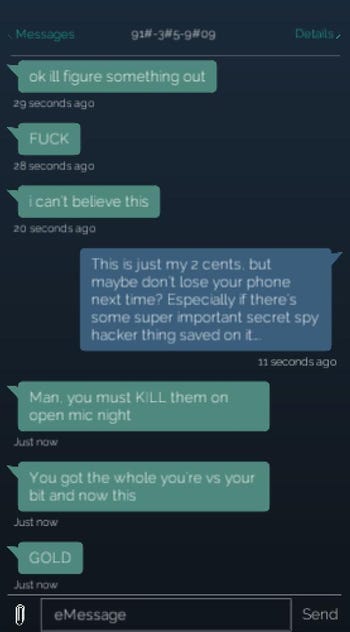

Now, if you already admonished her for screwing up “your”, Darlene will say:

But if you didn’t, she’ll give you a more generic response:

THE WONDERS OF INTERACTIVE STORYTELLING! I’m sure this all seems extraordinarily obvious and kind of dully simple, but, trust me, stuff like this this works gangbusters to help forge the illusion that you’re talking to a real person, or, at the very least, a highly intelligent house plant.

KEVIN RIACH: From a design perspective, these types of storytelling tricks are the backbone of producing a complex narrative. While technically it is just a simple boolean value being tracked, it does become incredibly challenging to remember the increasingly complex web of story callbacks and the branches they create. We do our best to track these type of things in documentation, but so much of the burden rests on writers and designers planning things out early and playing the game often.

On Exfiltrati0n, we sometimes found ourselves bouncing into complex threads of choice sets that could cause the game to break. Retracing a player’s steps and knowing where these callback points exist quickly becomes an invaluable skill during the design process.

Misdirection

No tags.