The IGDA Switzerland Chapter hosted its second themed Demo Night in Lausanne on Wednesday 10th August (you can read about the first music themed event here). The event focussed on the theme of ‘death and consequence’ in game design, and was hosted in collaboration with the Game Developers Suisse Romande meet-up with generous support from the Swiss Arts Council, Pro Helvetia, and the Swiss Game Developers Association (SGDA). An international line-up of developers was invited to share its perspective of death in games and explore how this much theorised design element has evolved from a benign consequence of losing during gameplay.

The evening’s line-up was composed of special guests, co-director of That Dragon, Cancer (2016), Josh Larson; prolific game designer and academic, Pippin Barr; and Attila Szantner, CEO and Cofounder of Geneva-based Massively Multiplayer Online Science (MMOS)—the developer behind Project Discovery, which is integrated into EVE ONLINE (2003) by CCP Games. Switzerland’s indie community was represented by Philomena Schwab who talked about Niche: A Genetics Survival Game by Team Niche; Elias Farhan presented Splash Blast Panic by Team KwaKwa; and David Javet discussed Stonebond: The Gargoyle’s Domain.

Each presenter was asked the same set of questions to allow the audience to make easy comparisons:

How many times does death occur in your game?

What is the player's intended experience of death (fun, tragic, irritating, etc.)?

What are the principal game mechanics for creating these experiences?

What are the lasting consequences to players as a result of death in your game?

Please note that this article is more a dissertation than a straightforward write-up of the event, and features supplementary material to emphasise certain concepts.

<iframe title="That Dragon, Cancer Launch Trailer" src="//www.youtube.com/embed/60ZCaupyHhc?enablejsapi=1&origin=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.gamedeveloper.com" height="360px" width="100%" data-testid="iframe" loading="lazy" scrolling="auto" class="optanon-category-C0004 ot-vscat-C0004 " data-gtm-yt-inspected-91172384_163="true" id="889143676" data-gtm-yt-inspected-91172384_165="true" data-gtm-yt-inspected-113="true"></iframe>

Losing a Loved One

The first presenter was Josh Larson who Skyped-in from Des Moines, USA, to talk about That Dragon, Cancer —an award-winning and critically acclaimed game created by Josh, Amy and Ryan Green, and a small team under the name Numinous Games. That Dragon, Cancer is based on Amy and Ryan Greens autobiographical experience of raising their son, Joel, who was diagnosed with terminal cancer at the age of twelve months. Joel was only given a short time to live, but continued to survive for four more years before eventually succumbing to the cancer in March 2014.

While black cancerous forms scattered throughout the game at regular intervals serve to visualise the family’s threat, death only occurs once in That Dragon, Cancer and it’s a deeply harrowing experience. The development team set out to create a universal story that goes beyond the experiences of the Greens’—relatable to every player’s experience of loss. Josh kindly shared his personal experience of losing a loved one to illustrate that such sad situations can also contain moments of positivity—much like a tragicomedy that offers humour to offset an emotionally oppressive situation. For instance, thinking of a loved one can trigger the memory of a funny situation. Josh also highlighted that people deal with death in different ways. Players of That Dragon, Cancer find that Amy remains doggedly optimistic while Ryan’s tendency is to confront the facts—often withdrawing into an empty space of contemplation.

That Dragon, Cancer (2016), by Numinous Games, presents players with a sequence of varied gameplay vignettes that explore every facet of dealing with death—from moments of optimism and joy (left) to withdrawal and sorrow (right).

A Sequence of Gameplay Vignettes

Conveying such multifaceted experience of death would not be possible if Josh and the team had focussed on one core gameplay mechanic—as is typical in most video games. That Dragon, Cancer is therefore composed of a sequence of gameplay vignettes that explore the emotionally complex nature of losing a loved one. Fleeting moments of happiness, triumph and optimism are contrasted with moments of sorrow and reflection using gameplay mechanics to convey each aesthetic. For example, a Mario Kart-style driving sequence (above left) elicits joyous activity from players but is contrasted by moments of relative stillness when players are tasked with exploring a desolate hospital or find Ryan adrift in an emotional abyss (above right).

Each gameplay vignette works in combination with the whole to create a poignant reflection on death. Without wishing to give too much away about the game’s ending, players are offered an interactive space in which they can dwell for as long as they wish to express themselves and vent their feelings.

Lifting the Taboo

The lasting consequences to players of That Dragon, Cancer is a very real confrontation with mortality and the transitory nature of life. Josh found a particularly heart-warming discussion forum in an unlikely place: the comments section of a That Dragon, Cancer “let’s play” YouTube video. What was surprising—other than the uncharacteristically amiable comments—was that users were talking openly about their personal experiences with cancer. It seems that That Dragon, Cancer gives people the confidence to speak about a topic that is somewhat of a taboo (in the U.S., at least). This is an achievement that the video games industry should celebrate.

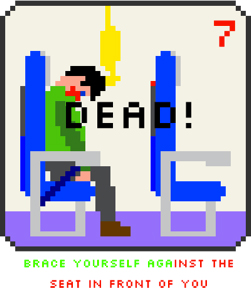

Safety Instructions (2011), by Pippin Barr, takes a whimsical look at death in video games by encouraging players to experience the various ways that a passenger can die in an airline accident.

Interactive Commentary on Death

Pippin Barr was the second presenter of the evening—Skyping-in from Montreal, Canada, to talk about his portfolio of interactive commentary on death in games. Pippin is well-known for creating games that reflect on the nature of games—such as the recently released Game Studies (2016), which he developed together Jonathan Lessard to lampoon five game design theories.

The first game that Pippin presented was Safety Instructions (2011). Inspired by Sierra Nevada titles like the Space Quest and the Leisure Suit Larry series, Pippin’s game encourages players to blunder through inflight safety instructions and cause the on-screen airplane passenger to suffer a multitude of whimsically presented deaths. Pippin stated self-deprecatingly that this was “the last fun game [he] made.” In stark contrast to That Dragon, Cancer presented by Josh, Safety Instructions is an explicit reference to the carefree treatment of death in the majority of video games. Death can occur an infinite number of times with repetition: the player passenger can explicitly die in 9 unique ways; two other people can die according to the player’s actions; and there are two ambiguous endings that allude to a watery end. The player’s takeaway is pure entertainment.

A Series of Gunshots (2015), by Pippin Barr, solicits players to user their imaginations and evoke personal images of murder.

Death in the Players’ Imagination

A Series of Gunshots (2015)—created four years after Safety Instructions—saw Pippin return to the theme of death, albeit with a significantly more serious tone matched by the sombre colour palette of the game’s visuals. A Series of Gunshots features five scenes in a play-through and players can fire 1-3 gunshots in each scene. Death is not explicitly represented in the game. Only muzzle flashes can be glimpsed through windows. The reasoning behind these game design decisions is to create a life-like representation of death by evoking the act of murder in the players’ imagination after they’ve pulled the trigger. The possibility to fire 1-3 gunshots has a performative function that further nourishes the players’ imagination, since one shot fired will stir-up different imaginings to three successive blasts.

Restart Times

The final design element that affirms A Series of Gunshots’s intentions as a commentary on the real repercussions of death is that the game installs a browser cookie that can prevent players from replaying the game successively and experiencing