,

,The following excerpt comes from author David L. Craddock's Long Live Mortal Kombat, the definitive account of the MK franchise's creation and its global impact on popular culture, funding now on Kickstarter.

The enmity between Nintendo and Sega defined the 16-bit console war of the 1990s, but there were theaters within the larger scope of that grand epic. Mario versus Sonic was one. Street Fighter II's World Warriors against the kombatants of Mortal Kombat was another.

Both pugilistic franchises had their strengths. Mortal Kombat was notoriously violent and flashy. Street Fighter II was mechanically complex. Mortal Kombat's characters and lore evolved from game to game, sequel to sequel. Capcom refined Street Fighter II's basic and special attacks over several iterations. Some of my friends favored one and turned their noses up at the other. I was the peacemaker, bravely crossing the aisle of local arcades or living rooms to proselytize my "Why not both?" style of thinking. (Although I confess I preferred MK's grittier aesthetic and more aggressive style of play.)

If you were the purveyor of either franchise, you couldn't afford to adopt that mentality. At least that was my thinking. In researching Long Live Mortal Kombat, I asked my contacts from Midway and Acclaim, which brought MK1 and MKII to home platforms, for their thoughts on Capcom's prizefighter. Their line of thinking was, to paraphrase, that SFII was good, but Mortal Kombat was a different beast. Starker, and in possession of characters that players actually cared about as co-creators Ed Boon and John Tobias spun yarns from game to game. Look at the attract mode—those demos that played when no players were around to feed machines quarters—and you got sucked into Mortal Kombat's supernatural world. Street Fighter II's attract mode revealed such scintillating details as Ryu's height, weight, and blood type. Riveting stuff, but it got me thinking: What did Capcom think of Mortal Kombat?

Mario versus Sonic, Command & Conquer versus WarCraft II, and Street Fighter versus Mortal Kombat. Just a few of the video game rivalries that defined the 1990s.

The answer is googleable, and google it I did, but I wanted to talk to someone who was on the front lines of one of the hottest battles that continues to this day—and one that, in the '90s, had a major impact in the conflict between Sega and Nintendo.

Enter Joe Morici, the senior vice president of Capcom USA during one of the company's most pivotal eras. I knew of Joe through an anecdote shared with me by Acclaim co-founder and president Rob Holmes, who smiled gleefully as he recalled buying all available ad space in an issue of Capcom's Street Fighter II comic and plastering it with advertisements for Acclaim's forthcoming Mortal Monday, a $10 million marketing blitzkrieg that saw the first MK arrive on Super Nintendo, Sega Genesis, Game Boy, and Game Gear weeks before Street Fighter II hurricane-kicked its way onto Sega's 16-bit console for the first time.

Joe and I talked Capcom's friendly feud with Acclaim, the cultural differences between Capcom USA and Capcom Co., Ltd., in Japan, and, of course, Street Fighter versus Mortal Kombat. (Spoilers: He's a Street Fighter soldier.)

David Craddock: How did you get involved in the video game industry?

Joe Morici: I'm dating myself, here. I worked for a company initially called Universal USA. which [made games such as] Mr. Do! and Mr. Do's Castle. They had a job offering in the newspaper. I was working as a vice president in banking, which I hated. I went and interviewed with a guy named Mac Sugita, who was the president of the company, and I got the job as a regional sales guy. That was the early 1980s. Universal USA was a small Japanese game manufacturer that was from Tokyo. A guy named [Kazuo] Okada-san owned Universal.

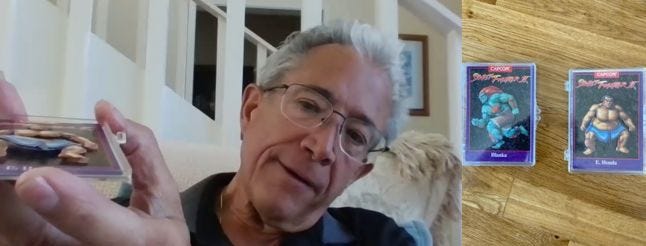

Morici shows off his custom-made Street Fighter II cards designed by artist Denny Moore. Moore used layers to make them appear three-dimensional when viewed at an angle. (Photos courtesy of Joe Morici.)

Craddock: How did you make the jump from Universal to Capcom USA?

Morici: At Universal, we were having trouble getting distribution through the different arcade distributors across the country. There was resentment or hesitation to buy Japanese products 80s, so we opened up our own distribution company. We had four offices. I started that division because I started calling on the operators directly and bypassing the distributors, so we became our own distributor, Universal Distributing Company. We would grey-market games in from Bally, Sente, all the different manufacturers. We were hurting other distributors' business because I was doing it and I was having pretty good success. Sugita leaves, and George Nakayama comes in to run Universal. A guy named Will Laurie, who was the president of Bally Advance in San Francisco, called me and said, "Let's go have lunch." He made me an offer to go to work for Bally Advance as the sales manager. They offered a $25,000 raise. I went back to George and said, "If you match their offer, I'll stay." He said no.

I left Universal and went to work for Bally. I was the youngest guy there by far. I was managing a bunch of older gentlemen. Bally handled everything: coin-op, cigarette machines, any sort of vending machine, pool tables. I was there for a few years. At that point, Nakayama [had left Universal and] was the president of Capcom, USA. He calls me on the phone and he says, "I want you to work with us." I said okay, but I knew a guy named Ron Carrara, who was a good friend of mine, and who was running Bally Advance [following the departure of Will Laurie], write me a letter that gave me a $25,000 raise. I took that letter back to Nakayama and I said, "You match this offer, and I'll work with you." He did, so I got the $25,000 raise twice.

I joined Capcom and became the regional sales manager of Capcom coin-op, because there was no Capcom consumer branch. We released a bunch of coin-op games, and one was Street Fighter. Do you remember the first one with the rubber mallets?

I told the marketing company, " Look, typically, we don't go against competitors this way, but—go against Mortal Kombat. I don't really care what you do, just show Mortal Kombat getting crushed."

Craddock: I do, yeah.

Morici: We took it off the market because people were getting hurt. That's why we put the buttons on there. Nintendo was getting started [in the video game business], and George Nakayama asks me, "Would you want to run the consumer division?" I said, Yeah, okay, fine. Why not? I mean, I knew deep down that the coin-op industry, once Nintendo got stronger, would be pretty much nonexistent. But back then, the coin-op business was huge. There was an arcade game in every corner store, every laundromat, because they were making good money. Street Fighter was making well over $1,000 a week. You're talking $4,000 a month [per cabinet]. That's a lot of money for one game.

I start the consumer division, and it was just me at first. I started hiring people, regional sales guys, across the country. Most of them were independent salespeople because the [consumer games] industry was new, so we [Capcom USA] were one of the first licensees of Nintendo. It was us, Bandai, Namco, and Konami. We started selling games. The first ones we had were conversions of Ghosts 'n Goblins, 1942, Commando. These were great coin-op games we converted over to the consumer division, which was what Capcom did. We were using the coin-op business as a testing ground for the home market. The thinking was that if a game did well as a coin-op, it would do well as a consumer title. That's really what happened.

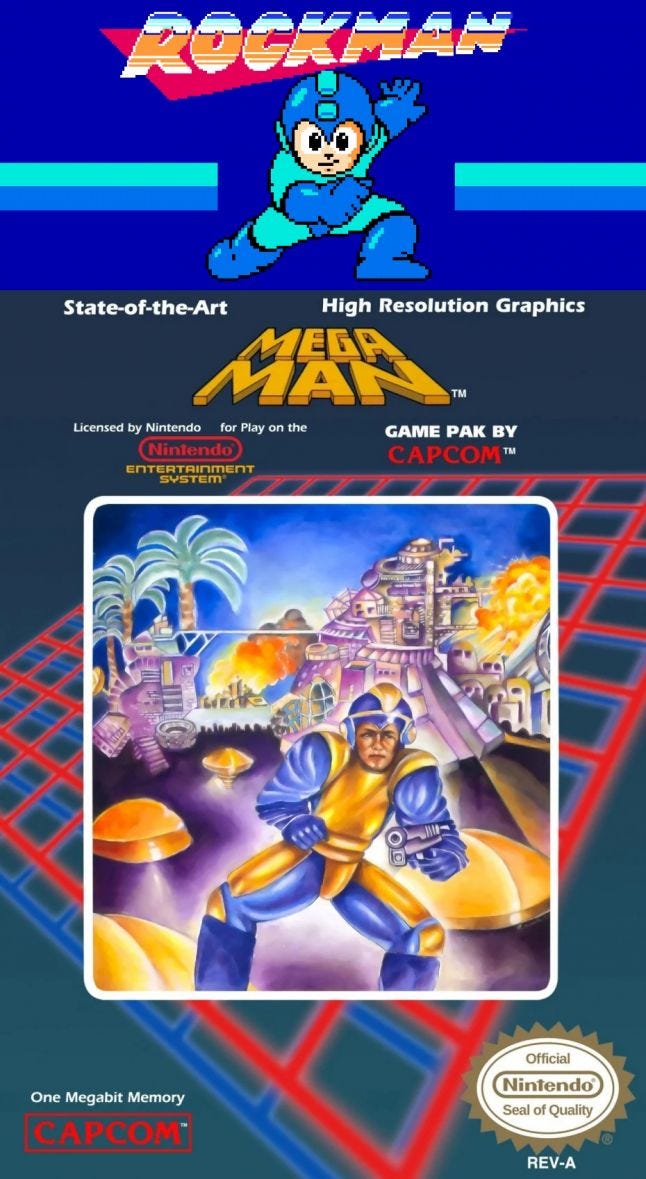

This was before the Street Fighter II phenomenon, and before Mega Man. That's the game I get grief about all the time for changing the name. That didn't make sense.

Mega Man's name change took time to sink in. The original game's box art still hasn't resonated.

Craddock: I've always wondered about that. What was your motivation for changing the character's name from Rock Man to Mega Man?

Morici: Rock Man came over and I thought, Rock Man doesn't make any sense to me. I knew the characters were based on rock musicians and stuff, but I thought, Let's just change the name. At that point, Capcom [Japan] trusted me to do the right thing for the US market, so I changed the name to Mega Man. It really wasn't this long, drawn-out discussion with everybody in the office. I just said, "Yeah, let's change it." So we did. I don't know why people get so upset about it. It just made sense to me.